Overview

|

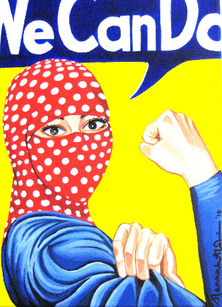

Both today and historically, Muslim women across the world have been involved in varied efforts to improve the status of women and tackle practices or attitudes that are considered discriminatory on the basis of gender.

|

This website will explore what feminism in Islam can mean to different people and how it might challenge stereotypes both in Islam and feminism, as well as the perceived clash between the two.

|

This resource was released to coincide with Women’s History Month which is celebrated worldwide every March. Women’s History Month is a time to question conventional accounts of the past. Whether in relation to war, the arts, science, education or politics, these accounts will frequently have something in common - the absence of women.

We have history. But what of ‘herstory’?

We have history. But what of ‘herstory’?

Arrows may not center when in edit mode. Once site is published, the arrow will be centered on the tab

When the site is published, this border and note will not show up.

Drag & drop your tab 1 content here

Introduction

There are roughly 1.6 billion Muslims across the planet – that is almost a quarter of the world’s population and an extraordinarily diverse mass of people. Muslim women, as approximately half of this group, vary in all ways imaginable. From dress style and fashion to professions, hobbies and their relation to their faith, Muslim women are as diverse as womankind as a whole.

Both today and historically, Muslim women across the world have been involved in varied efforts to improve the status of women and tackle practices or attitudes that are considered discriminatory on the basis of gender.

|

For many of these women, feminism - or striving for gender equality - has been compatible with their identity as Muslims. They may describe themselves as ‘Muslim feminists’ or as believing in ‘Islamic feminism,’ although others may not wish to define their efforts or attitudes in this way. Feminism may not appeal or be seen as necessary by many Muslim women, in the same way that many women across the world feel no affiliation with feminism, or would not label themselves ‘feminist.’

Feminism among Muslim women, like feminism among non-Muslim women, is hugely varied and one common vision of what gender equality is in Islam should not be assumed. Muslim women vary in race, social class, culture, and as people, and may range considerably from those following Islam in a typically conservative way to women with a more liberal lifestyle. |

Just as ‘Islam’ and ‘feminism’ mean different things to different people, Muslim women are also diverse in their attitudes and identities, and how they understand and express feminism. For many women it has allowed them to identify with both Islam and feminism without feeling that they have to compromise either part of their identity.

Over history, there have been movements of women and men from diverse Muslim backgrounds united by their desire to reclaim what they see as Islam’s true spirit of justice when it comes to gender relations. These individuals have interrogated stereotypes about women and Islam and provided compelling gender-sensitive readings of holy texts to separate religion from patriarchy. 'Patriarchy' means a system or society of male dominance. |

These thinkers stress how 'rigid' understandings of what Islam or feminism might mean can often deny non-Muslim and Muslim women across the world the right and opportunity to find their own voice.

This resource will explore what feminism in Islam can mean to different people and how it might challenge stereotypes both in Islam and in feminism as well as the perceived clash between these two areas.

This resource will explore what feminism in Islam can mean to different people and how it might challenge stereotypes both in Islam and in feminism as well as the perceived clash between these two areas.

Drag & drop your tab 2 content here

Context: Muslim women in the UK

Just as the notion of gender equality is the subject of ever-changing debate in societies across the world, there is no simple ‘solution’ to gender equality debates in a Muslim context.

|

What is commonly referred to as ‘first wave of feminism,’ emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries in America and Europe. Over time however, the claim of this mainstream feminism to represent all women was challenged by women from different backgrounds who felt it did not and could not represent their experiences. |

The many types of feminism which have since emerged and continue to do so - radical, African American, anarchist, queer, liberal, black, postmodern and post-colonial, to name a few - indicate that feminism is not as ‘universal’ as some would make out.

The idea that a ‘universal womanhood’ cannot apply to the lives of all women across the world led to the birth of the theory of 'intersectionality.’

Intersectionality is an academic concept that recognises that women from different backgrounds are subject to different layers of oppression. A black, lesbian woman who is disabled for example is subject to discrimination on the grounds of her race, sexuality and disability, as well as her gender.

Muslim women face a double discrimination on the basis of both their gender and their faith.

In some Muslim countries practices that are discriminatory against women such as FGM, unequal rights in marriage and divorce and the idea of ‘fixed gender roles’, are defended in the name of religion and often enshrined in law. These practices, and the attitudes surrounding them, can be found in Muslim communities across the world, including here in the UK – some being described as ‘cultural’ and some being ‘religious.’

The multitude of negative stereotypes about women and Islam can make it appear that feminism has no place in Islam. Talking about empowering Muslim women can therefore be difficult.

The idea that a ‘universal womanhood’ cannot apply to the lives of all women across the world led to the birth of the theory of 'intersectionality.’

Intersectionality is an academic concept that recognises that women from different backgrounds are subject to different layers of oppression. A black, lesbian woman who is disabled for example is subject to discrimination on the grounds of her race, sexuality and disability, as well as her gender.

Muslim women face a double discrimination on the basis of both their gender and their faith.

In some Muslim countries practices that are discriminatory against women such as FGM, unequal rights in marriage and divorce and the idea of ‘fixed gender roles’, are defended in the name of religion and often enshrined in law. These practices, and the attitudes surrounding them, can be found in Muslim communities across the world, including here in the UK – some being described as ‘cultural’ and some being ‘religious.’

The multitude of negative stereotypes about women and Islam can make it appear that feminism has no place in Islam. Talking about empowering Muslim women can therefore be difficult.

|

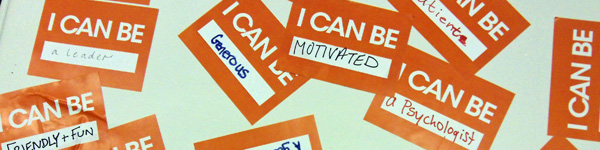

Maslaha’s I Can Be She campaign seeks to challenge misconceptions about what it means to be a Muslim woman both in Muslim and non-Muslim communities and empower women and girls to demand change. Introducing young girls to a wide range of role models and capturing the diverse stories and spirit of British Muslim women today was a large part of this.

|

What are the issues surrounding the idea of feminism in Islam?

|

2. Tensions with mainstream feminism: ‘Mainstream’ feminism has historically seen religion as incompatible with their demands for women’s equality and may be unwilling to associate with efforts that make arguments within a religious structure. A lot of secular feminists see Muslim feminists as a group in need of liberation. |

|

3. Tensions within Muslim communities: Feminism is frequently seen as a ‘western’ import which is alien to Islam and threatening to Muslim values. ‘Women’s rights’ or ‘feminism’ have been used to justify colonial policies and the invasion of Muslim countries, both historically and also in recent times. This means feminism has a negative image in many Muslim communities. |

Drag & drop your tab 3 content here

Key concept: equality

Here in the UK, as in many countries, women are granted ‘equality’ in law with men. This is known as 'formal equality' and is very important as it shows that we as a society are working towards a world where discriminatory practices are eliminated.

However, daily life and realities may look quite different - even in countries where men and women are equal before the law.

However, daily life and realities may look quite different - even in countries where men and women are equal before the law.

Take the UK Feminista pledge!

Take the UK Feminista pledge!

Here in the UK for example, issues like sexism in the workplace and in schools, sex trafficking, pornography and sexual violence such as domestic violence, assault and rape are unfortunately very common. The practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) continues amongst some communities, despite it being illegal and tireless efforts of campaigners to end the abuse. Nobody in the UK has ever been convicted of violence relating to FGM.

Increasingly, feminists emphasise the importance of moving beyond formal equality in law and embracing a more 'transformative equality' that can change the daily realities of women.

|

This requires a change in what many people have taken for granted - a transformation of attitudes about, and opportunities for, women and men in the home and in different important institutions, for example the government or in workplaces and schools.

Changing attitudes however is not easy because attitudes are linked to gender stereotypes. Gender stereotyping means to expect particular roles or behaviour from men and women without considering a person’s actual talents, desires or preferences - without considering their own autonomy. |

Watch a film with Hannah Habibi

|

|

Women for example will be nurturing and sensitive. They need protecting and are suited to particular jobs and should look a particular way, in terms of dress and manner. Men on the other hand are leaders and breadwinners; they are more rational than women and less emotional (supposedly). These unconscious expectations can be seen as 'unwritten rules' and filter into all aspects of life.

|

Drag & drop your tab 4 content here

Key concept: gender stereotypes

Stereotypes exist in every single country in the world and are often seen as natural by both men and women.

They are grounded in culture, tradition, religion, everyday attitudes and are perpetuated in the media, advertising and education. This contributes to expectations and assumptions of oneself and others.

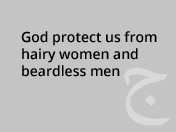

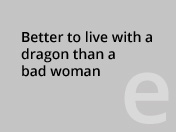

The proverbs, [1] or old sayings, below are from a variety of countries across the world. Despite the fact that these countries are perceived to be very different, the stereotypes show surprising similarities in how women are stereotyped.

They are grounded in culture, tradition, religion, everyday attitudes and are perpetuated in the media, advertising and education. This contributes to expectations and assumptions of oneself and others.

The proverbs, [1] or old sayings, below are from a variety of countries across the world. Despite the fact that these countries are perceived to be very different, the stereotypes show surprising similarities in how women are stereotyped.

Gender stereotypes are therefore not unique to Muslim communities, but they can be quite hard to challenge as they are often defended as 'religious,' rather than 'cultural.' This means that discussing them can be challenging. Some feminists[2] have argued that just like a doctor must name an illness before it can be treated – gender stereotypes also need to be ‘diagnosed’ before they can be addressed.

Male and female scholars and jurists have made challenging them possible because they have highlighted how social context - history, politics, tradition, culture – affected the translation of holy revelation (the Qur’an) into actual laws in Muslim countries.

They are challenging discriminatory practices which have been defended in the name of Islam. They argue that these practices - such as unequal divorce rights and marrying girls off at a young age - aren't rooted in religion but are a result of social, cultural and political conditions.

This is important because these discussions can then be held within an Islamic framework, and open up a space for critical thinking.

Male and female scholars and jurists have made challenging them possible because they have highlighted how social context - history, politics, tradition, culture – affected the translation of holy revelation (the Qur’an) into actual laws in Muslim countries.

They are challenging discriminatory practices which have been defended in the name of Islam. They argue that these practices - such as unequal divorce rights and marrying girls off at a young age - aren't rooted in religion but are a result of social, cultural and political conditions.

This is important because these discussions can then be held within an Islamic framework, and open up a space for critical thinking.

Drag & drop your tab 5 content here

Feminism in Islamic history

Islam was revealed in the 7th century CE. At this time, many progressive reforms were made to improve life for women and girls, some of which did not reach European countries until much later.

This included the banning of ‘female infanticide’ – where baby girls were killed at birth as boys were seen as preferable. Women’s reproductive rights, their rights in the inheritance of property, and also in divorce and marriage also improved.[1]

Scholars such as Leila Ahmed have described how while 1,400 years ago Muslim women had the right to own and dispose of property and earnings, in England it was not until the Married Women’s Property Act was passed in 1882, that women were given the right to keep their property after marriage.[2]

The writers Haddad and Esposito said: ‘Muhammad granted women rights and privileges in the sphere of family life, marriage, education, and economic endeavours, rights that help improve women's status in society.’[3]

Continuation of a progressive tradition?

A lot has been written on the positive changes Islam brought to the lives of women during its early years.

However this positive tradition is poorly reflected today when we look at the family laws and attitudes towards women in Muslim countries and in some Muslim diaspora communities across the world, including here in the UK.

Male and female Muslim scholars from a wide range of standpoints, such as Fazlur Rahman, Khaled Abou El Fadl, Abdullahi An-Na'im, Azizah Al-Hibri, Shuruq Naguib and Amina Wudud, have offered explanations of why this may be the case.

These explanations bring to light the ways in which the interpretation of Qur'anic revelation into laws was heavily influenced by the patriarchal milieu of the time. Unveiling the social construction of how laws are formed and the subjective ideologies, political, sociological, cultural, economic and historical factors that informed these has been key to such efforts.

Muslim feminists have argued that human interpretations of Qur'anic revelation into laws do not reflect Islam's innate sense of social justice and the realities of the lives of Muslim women across the world.

Reforms

While in some Muslim countries such as Tunisia, Morocco, Indonesia and Turkey, these laws have been reformed in ways, in others they have been changed little because they are believed to be religious - Islamic - and therefore untouchable.

The presence of such laws adds to the negative stereotypes about how Islam views women and validates the continuation of discriminatory practices against women in Muslim communities across the world, including here in the UK. For example, in Egypt if a woman wants to divorce she must first get a judge's approval, where as a husband does not have to do the same.[4] Or in Kuwait, the minimum age for girls to get married is 15.[5]

There are many scholars, women’s groups, and activists, such as Musawah, working today to emphasise that gender equality in the Muslim family is necessary and possible.

If we look back, we can see that Islam has a rich history of important figures and movements working for improving women’s rights and autonomy.

This included the banning of ‘female infanticide’ – where baby girls were killed at birth as boys were seen as preferable. Women’s reproductive rights, their rights in the inheritance of property, and also in divorce and marriage also improved.[1]

Scholars such as Leila Ahmed have described how while 1,400 years ago Muslim women had the right to own and dispose of property and earnings, in England it was not until the Married Women’s Property Act was passed in 1882, that women were given the right to keep their property after marriage.[2]

The writers Haddad and Esposito said: ‘Muhammad granted women rights and privileges in the sphere of family life, marriage, education, and economic endeavours, rights that help improve women's status in society.’[3]

Continuation of a progressive tradition?

A lot has been written on the positive changes Islam brought to the lives of women during its early years.

However this positive tradition is poorly reflected today when we look at the family laws and attitudes towards women in Muslim countries and in some Muslim diaspora communities across the world, including here in the UK.

Male and female Muslim scholars from a wide range of standpoints, such as Fazlur Rahman, Khaled Abou El Fadl, Abdullahi An-Na'im, Azizah Al-Hibri, Shuruq Naguib and Amina Wudud, have offered explanations of why this may be the case.

These explanations bring to light the ways in which the interpretation of Qur'anic revelation into laws was heavily influenced by the patriarchal milieu of the time. Unveiling the social construction of how laws are formed and the subjective ideologies, political, sociological, cultural, economic and historical factors that informed these has been key to such efforts.

Muslim feminists have argued that human interpretations of Qur'anic revelation into laws do not reflect Islam's innate sense of social justice and the realities of the lives of Muslim women across the world.

Reforms

While in some Muslim countries such as Tunisia, Morocco, Indonesia and Turkey, these laws have been reformed in ways, in others they have been changed little because they are believed to be religious - Islamic - and therefore untouchable.

The presence of such laws adds to the negative stereotypes about how Islam views women and validates the continuation of discriminatory practices against women in Muslim communities across the world, including here in the UK. For example, in Egypt if a woman wants to divorce she must first get a judge's approval, where as a husband does not have to do the same.[4] Or in Kuwait, the minimum age for girls to get married is 15.[5]

There are many scholars, women’s groups, and activists, such as Musawah, working today to emphasise that gender equality in the Muslim family is necessary and possible.

If we look back, we can see that Islam has a rich history of important figures and movements working for improving women’s rights and autonomy.

Indeed, Dr. Sariya Contractor has noted that in 1917 the English writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, after meeting Turkish women, felt that they had so much more rights in society that she wanted to use their liberties as a stick to beat English society with.[6]

Lady Montagu also appears in Maslaha's Book of Travels online exhibition, based on the life and writings of the Ottoman traveller Evliye Çelebi. Experience 17th century Istanbul, Vienna and Cairo through their eyes with a deep-zoom video and audio tour. Delve into the exhibition at: thebookoftravels.org

While the term ‘feminist’ only emerged in the 19th century, these efforts show ‘feminism’ in different forms has always existed across Muslim communities in everyday reality. Feminism in Islam is not then an attempt to import ‘alien’ values in Islam; it is a rediscovery of what is already there and a reclamation of faith.

Lady Montagu also appears in Maslaha's Book of Travels online exhibition, based on the life and writings of the Ottoman traveller Evliye Çelebi. Experience 17th century Istanbul, Vienna and Cairo through their eyes with a deep-zoom video and audio tour. Delve into the exhibition at: thebookoftravels.org

While the term ‘feminist’ only emerged in the 19th century, these efforts show ‘feminism’ in different forms has always existed across Muslim communities in everyday reality. Feminism in Islam is not then an attempt to import ‘alien’ values in Islam; it is a rediscovery of what is already there and a reclamation of faith.

When thinking about inspiring female figures in the history of Islam, the first figure to come to mind is often the Prophet Muhammad's first wife, Khadija bint Khuwaylid, who was the second convert to Islam after Prophet Muhammad himself. Despite the patriarchal society she lived in, Khadija was a successful business woman and Prophet Muhammad was her employee. She was 15 years older than him and in defiance of social norms, both then and today, she was the one to propose to him! You can read more about her extraordinary story in Maslaha's Forgotten Heritage archives.

> Explore the lives and work of other Muslim women who have worked to improve women's lives and rights over history.

> Explore the lives and work of other Muslim women who have worked to improve women's lives and rights over history.

Case study: Egypt

Egypt, like most Muslim countries, has a rich history of diverse feminism.

Here we explore the conversations between 19th century feminists, both religious and secular.

Read more >

Here we explore the conversations between 19th century feminists, both religious and secular.

Read more >

[1] John L Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path (2005) p. 79

[2] Ziba Mir Hosseini in 'Wanted: Equality and Justice in the Muslim Family' (2011) p. 37

[3] Yvonne Haddad and John L Esposito, Islam, Gender and Social Change (1998) p. 168

[4] Musawah Thematic Report on Article 16: Kuwait & Oman (2011) see p. 4

[5] UN Women website: Declarations, reservations and objections to CEDAW - see section on ‘Egypt’

[6] Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor 'Recognizing Muslim Women's Voices', Public Spirit (2014)

[2] Ziba Mir Hosseini in 'Wanted: Equality and Justice in the Muslim Family' (2011) p. 37

[3] Yvonne Haddad and John L Esposito, Islam, Gender and Social Change (1998) p. 168

[4] Musawah Thematic Report on Article 16: Kuwait & Oman (2011) see p. 4

[5] UN Women website: Declarations, reservations and objections to CEDAW - see section on ‘Egypt’

[6] Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor 'Recognizing Muslim Women's Voices', Public Spirit (2014)

Drag & drop your tab 6 content here

Feminism in Islam today

The last three decades have seen a dynamic and multi-stranded wave of academic thought grow in prominence, which is frequently referred to as ‘Islamic feminism.’

This has been described as:

“New voices and scholarship in Islam that are feminist in their aspirations and demands and Islamic in their source of legitimacy. These voices herald a new phase in the troubled relationship between Islam and feminism.” [1]

This has been described as:

“New voices and scholarship in Islam that are feminist in their aspirations and demands and Islamic in their source of legitimacy. These voices herald a new phase in the troubled relationship between Islam and feminism.” [1]

|

Not all Muslim female thinkers associated with 'Islamic feminism' however, affiliate with the term. Professor Asma Barlas, for example, is frequently described by others as 'an Islamic feminist,' but she herself does not choose to identify in this way.

This section aims to introduce key voices and ideas that have come out of this movement. It should be noted that some of these thinkers have been celebrated and others seen as controversial by different sections of Muslim communities. |

Although the academic discourse around the concept 'Islamic feminism' is fairly recent, Muslim women (and men) have been challenging everyday realities in their own ways for centuries.

The thinkers and ideas below are complemented by a set of videos of women today, who explain their own perspectives and experiences of Islam and feminism in everyday life. Although quite separate from academic discourse, everyday realities are feeding in to new theories and vice versa. |

By bringing 'Islamic feminism' out of the realm of academia, and onto the streets, new spaces for discussion can be opened up.

> Find out how women today are engaging with Islam and feminism at a grassroots level and through academia.

> Find out how women today are engaging with Islam and feminism at a grassroots level and through academia.

Muslim family laws

Groups like Musawah, point to the distinction between fiqh and Shari’ah and how this reflects in their work for gender equality and understanding Muslim family laws.

Groups like Musawah, point to the distinction between fiqh and Shari’ah and how this reflects in their work for gender equality and understanding Muslim family laws.

- In Islam, the word Shari’ah means God’s will as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Shari’ah law is considered to be holy, timeless and unchangeable.

- Fiqh – on the other hand means the human effort to extract legal rules from the holy sources of Islam – the Qur’an and Sunnah. Over the centuries the jurists who have worked to do this have been influenced by their cultural, political and social context and experiences. While Shari’ah is holy, Fiqh is human and contestable.

- As a product of Fiqh, Muslim family laws are not immune from criticism or reassessment. Encouraging this understanding has proved useful as it allows these laws and practices to be criticised and debated within a religious framework.

[1] Ziba Mir-Hosseini, 'How to challenge patriarchal ethics of Muslim legal tradition' (2013)

Drag & drop content here